Hate is low-hanging fruit, and by generalizing the other and not giving them a face, we dehumanise those who are different from us. Bollywood propaganda films risk tarnishing the industry’s storytelling legacy by replacing nuance and diversity with shallow, divisive narratives.

With the way things are going in the world these days, there’s nothing much that should surprise anyone. So, that feeling after watching Akshaye Khanna, an actor’s actor if there ever was one, portray the essence of evil, as Emperor Aurangzeb in Chaava, it wasn’t surprise.

Resignation? Perhaps.

Heartbreakt? Absolutely. But surprise? No. We’re too far down the road to be surprised much anymore, except to look back at where we came from and wonder how we got here. Because we are in this journey with our idols, every step of the way.

If you’re like us, Bollywood haas played a huge part in your childhood too. It has shown right from wrong through the eyes of your idols on the big screen. When Jai and Veeru rode that motorcycle, you were the third wheel, singing “Yeh dosti hum naheen choraingay” just as loud as them.

When Raj told Simran that “Barray barray shehron mein aisy choty choty baaten hoty rehty hain,” you took his words as gospel and memorized them. To be used for whenever something bad happened later in life.

Growing up, we never had to think twice about the religious beliefs and ideologies of the heroes and heroines we idealized. They were just cool as they were. It never entered our mind to think if being Anthony Gonsalves meant adhering to a faith different from the one we were born with. We all wanted to be Amitabh Bachchan, not because he belonged to a certain sect, but because he was Vijay Dinanath Chauhan in Agneepath, Iqbal Aslam Khan in Coolie, Badshah Khan in Khuda Gawah,among so many other iconic roles that were unfettered by the boundaries of faith or geography.

But, on the off chance that you didn’t get to be Bachchan. Even if you got pipped by someone with a better costume, dialogue delivery or physical characteristics, you knew that all wasn’t lost. After all, getting a chance to play Rishi Kapoor’s Akbar or even Vinod Khanna’s Amer wasn’t a bad deal at all. The point being, religion never played a card in deciding who we wanted our heroes and heroines to be. So that when Rishi Kapoor as Monty in Karz says: “Meri umar ke naujawanon, dil na lagana aye deewanon,” we believed him and collectively shouted Om shanti om without thinking what it meant because it wasn’t the words, but the essence of the person saying them that became an anthem for a whole generation of kids, nicknamed Monty by their parents who had Rishi Kapoor and Neetu Singh posters on their walls when they were kids. When Mithun Chakraborty sang “I am a disco dancer,” a whole generation turned their lives into a song with a killer soundtrack by Bappi Da.

And then, slowly but surely, somehow, it all changed.

So, no, when Chaava came out, we weren’t surprised. We’d already seen Fighter, Gaddar 2, Mission Majnu, and so many other movies. But we won’t lie, we did feel a bit nostalgic. For a bygone time when the same actors, or even their fathers, many of whom had roots in the same land that they were now vilifying.

Down the Rabbit Hole

While our story began much earlier, but for the sake of storytelling, let’s begin from two recent events. The first one concerns the theatrical launch a film centered on the 2002 Godhra train burning, which was attended by Prime Minister Modi and his entire cabinet. The second incident concerns Anupam Kher and filmmaker Hansal Mehta engaging in a heated Twitter exchange revolving around The Accidental PM, a film featuring Kher that has been criticized as one of Hindi cinema’s worst examples of media manipulation.

These two incidents — one a grand political endorsement of a controversial story and the other a public clash over a film’s possible agenda — highlight a growing concern about how cinema is being harnessed to frame or taint public perceptions. It seems while we were growing up, Bollywood, the gateway to our childhood, entered into the era of propaganda films.

To be fair, propaganda films have been around for a long time. It’s just that they’ve never before waded so unequivocally into shredding apart the very fabric that had always covered the milieu thriving within. In the simplest terms, a propaganda film is crafted to advance a specific agenda — political, religious, or cultural — and is often employed to mold perspectives or sway public sentiment. However, it is only in the last decade when they have become all pervasive and in many ways, adding to the malaise that afflicts Bollywood. Since 2014, India has seen a marked uptick in politically charged, ideologically driven movies, with more on the horizon for 2025 — one reportedly centered on Nathuram Godse.

It wasn’t always like this.

The Golden Years of Optimism

In 1959, before Yash Chopra had us all daydreaming about running in fields of red and yellow tulips and singing “Dekha aik khwaab,” he made his directorial debut with Dhool Ka Phool, which featured a now-classic song with a resonant lyric: “Tu Hindu banega na Musalman banega, insaan ka aulad hai insaan banega.” Rather than focusing on religious distinctions, Chopra emphasized a universal human bond — a message that deeply connected with a nation still reeling from the scars of Partition.

The film follows Abdul Rashid, a Muslim man who raises an abandoned Hindu child, promoting the idea of a “good Muslim” — an upstanding citizen and caring parent. This depiction mirrored the spirit of a newly independent India that saw itself as a secular, democratic, and plural society, one in which creative expressions such as literature, poetry, and socially conscious cinema flourished. Productions like Anarkali (1953), Chaudavi Ki Chand (1960), Mughal-e-Azam (1960), and Pakeezah (1972) further underscored this inclusive vision by presenting Muslim characters as inherently noble.

Also Read: Virasat: The Moonch That Revived Anil Kapoor’s Career

By the 1970s, the trope of Muslim protagonists as compassionate, upstanding citizens became a regular feature of mainstream Bollywood. Manmohan Desai’s Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), centered on three brothers separated at birth and raised in different faiths—Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity—cemented the theme of pluralism. Desai’s blockbuster concluded with the trio reuniting, an allegory for India’s hope to bridge divides and celebrate its diversity. When Rekha had us mesmerized with “In aankhon ki masti,” and Naseeruddin Shah was making our jaws drop as the titular character in Mirza Ghalib, something much more sinister hadhateful was coming just around the corner.

A Dangerous Precedence

While 9/11 undoubtedly contributed to a worldwide spike in Islamophobic narratives, such portrayals in Indian films stretch back much further. Films like Roja (1992), directed by Mani Ratnam, showed Kashmiri militants as one-dimensional, malevolent figures, without any effort to illuminate the broader sociopolitical context. A growing appetite for sensational storytelling became apparent over the following decade, evident in films such as Sarfarosh (1999), LOC: Kargil (2003), Veer-Zara (2004), Fanaa (2006), Kurbaan (2009), and New York (2009). Each movie, in one way or another, relied on broad stereotypes of Muslims, gradually normalizing these portrayals within Bollywood. Sometimes, its hard to decide what hurts more, that movies on such hurtful themes were made or that actors we grew up idealizing agreed to be a part of such ventures.

Rather than point fingers, it would’ve made sene to take stock and not get carried away in the maelstrom of hate and division that was spreading all over the world. But hate is a low-hanging fruit and by generalizing the other, by not giving it a face, we de-humanise those different from us, making it easier to reject them. If ever there was a time for all those movies and songs we had grown up singing to, to be enacted in real life. If there ever was a time for the heroes on the screen to step off the stage and become real life icons, to say that love knows no nationality and cannot be bound, this was it.

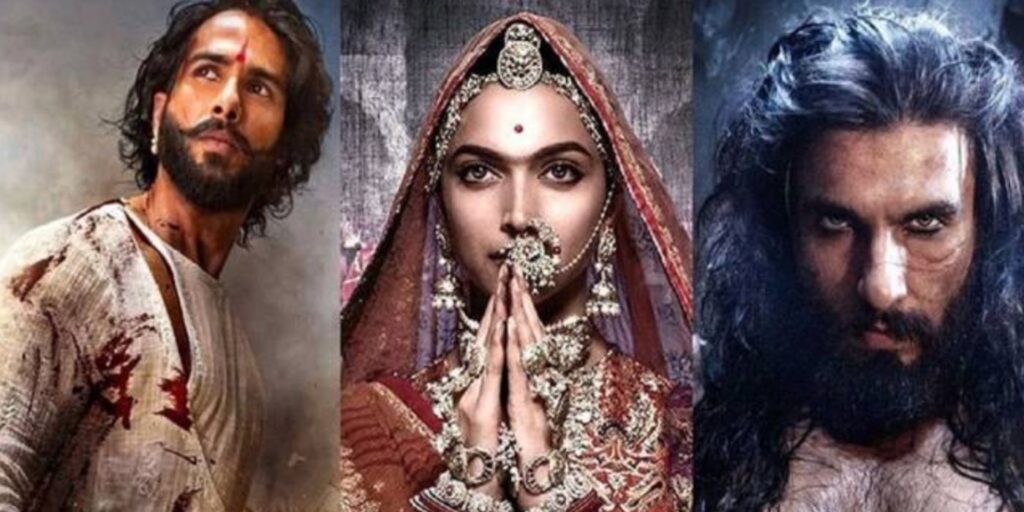

Then came 2014, and with it the floodgates opened with several releases that embraced overt Islamophobia and championed Hindu supremacy—particularly in large-scale historical dramas like Padmaavat (2018) and Tanhaji (2020), set during eras of India’s Islamic past. These films often showcased Muslim rulers as grotesque, excessively sexual, or unnaturally cruel, all under the guise of historical narrative—even when the source material was heavily fictionalized, to the point of being completely untrue.

A prime example is The Kerala Story (2023), which garnered controversy for insisting that 32,000 Hindu women had been manipulated into joining ISIS. Official data and research reports contradict these massive numbers, yet the film still presents an exaggerated narrative that reinforces conspiracy theories such as “love jihad.” Despite its polarizing impact, it was granted tax-free status in BJP-ruled states, underscoring the political support behind such content.

A similar pattern emerges around the 2002 Godhra train incident. Two commissions — the Nanavati and Banerjee Commissions — produced conflicting reports: one labeling the tragedy a deliberate attack, the other concluding it was accidental. Yet recent films like Sabarmati Report ignore the complexity and push the deliberate-attack angle. Apparently, the film had political backing and received tax exemptions, despite its lackluster performance and tepid critical reception, thus fulfilling the criteria of a propaganda film. The polarizing Kashmir Files also fits into this trend, heavily inflating death tolls and pointing the finger at a range of adversaries, including leftists and the opposition Congress Party.

This wave of cinema often features staple antagonists: medieval Muslim rulers, Islamist terrorists, Pakistan, left-wing intellectuals, and opposition parties. These films champion nationalism and Hindu pride, regularly glorifying certain figures while smearing political opponents. The 2019 release PM Narendra Modi is a case in point, painting the prime minister in glowing tones, whereas The Accidental Prime Minister depicted Dr. Manmohan Singh as a hesitant leader overshadowed by others.

Of course, political cinema in India predates the modern era. One early example might be Brandy Ki Botal, which supported Gandhi’s anti-alcohol campaign.It’s just that in recent times, movies have turned into mouthpieces for division and hatred rather than encouraging unity. In the post-independence period, movies like Bhagat Singh and Hamara Desh were intended to inspire patriotism and honor the freedom struggle. Older political movies might have championed social unity or pride in regional identity, but the latest crop goes further, deliberately targeting specific communities and misrepresenting history. These films aren’t merely creative endeavors but carefully engineered to sow discord and reinforce hateful narratives.

Not all recent films follow this path. Gully Boy, Haider, and Shahid offer more layered portrayals of Muslim lives, demonstrating that Indian cinema still has the capacity for depth and empathy. Nonetheless, the rising popularity of propaganda-heavy releases, combined with industry endorsements of hardline views, has normalized skewed representations.

Against this backdrop, actors and filmmakers who once embraced secular values—such as Anupam Kher—now frequently support narratives vilifying Muslims or demonizing Muslim voices advocating tolerance. The result is a troubling cinematic landscape where fact, history, and nuance often take a back seat to polarizing agendas.

Where Do We Go From Here?

There’s a scene in BluffMaster where Nana Patekar, while getting a shave, holds the blade, telling the barber “Yeh ustraa hai, isko uss tarah istemaal karo jiss taraah yeh hona chahiye.” The words are slightly paraphrased but the point is very apt here.

Cinema has long been a powerful force for shaping public perception, from wartime governments commissioning patriotic features to modern political parties running social media campaigns. In the wrong hands, it can destroy decades of work. Bollywood’s global reach only magnifies this impact. On average, Hindi films attract more than three billion viewers a year, surpassing Hollywood’s approximate 2.6 billion. Consequently, Bollywood not only influences the outlook of Indian audiences but also crafts an international image.

Between 2014 and 2024, the industry produced around 1,600 films and series—released both in theaters and on OTT platforms. Of those, approximately 1,000 included portrayals of Muslims in hostile or unfavorable roles.

Major titles from this period—Bajirao Mastani, Padmaavat, Tanhaji, Baby, Uri, Lipstick Under My Burkha, Secret Superstar, Gully Boy, Raazi, The Kashmir Files, The Kerala Story, Sooryavanshi, Animal, Omerta, 72 Hoorain, Panipat, Razakar, Godhra—and series like Sacred Games, Paatal Lok, Mirzapur, Tandav, The Family Man, Khuda Haafiz, and Bombay Begums further entrenched these themes by depicting Muslims or Islam in a negative light, whether through character stereotypes, antagonistic plots, or selective historical framing.

As someone who grew up on Bollywood songs and larger-than-life heroes who transcended borders and backgrounds, one can’t help but wonder: what would Amar, Akbar, and Anthony make of the world we live in today? Would Sher Khan from Zanjeer still lay down his life for Inspector Vijay Khanna? The hopeful part of us believes he would—unflinchingly. But the realist in us? Well, it suggests we might not want to hold our breath.

And yet, even as we tell ourselves not to, there’s a voice inside us that keeps humming a tune. It goes something like this: “Anhoni ko honi kardain honi ko unhoni..aik jagga jab jamma hon teenon…”